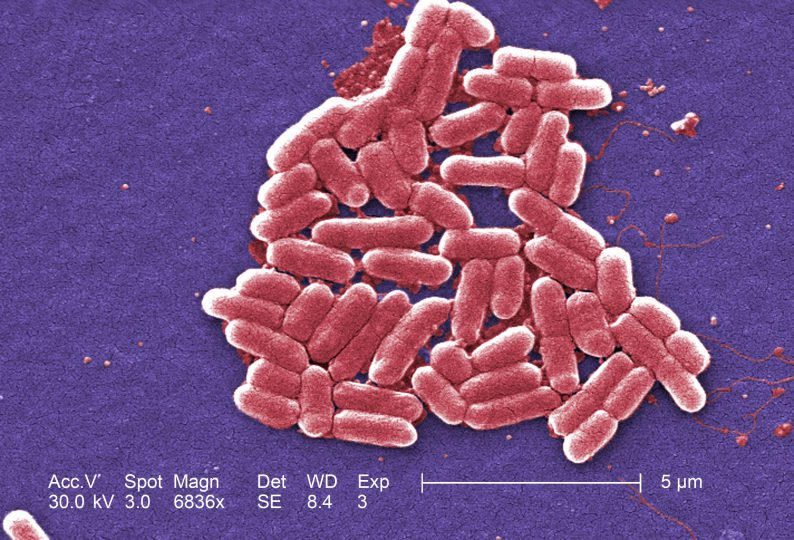

It’s been more than five weeks since the national Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) began investigating an E. coli outbreak that sickened 14 people in six states, including California, and has resulted in one death and yet the CDC has not been able to identify a source of the infections. It’s complicated.

County Epidemiology Program (EPI) staff—epidemiologists, communicable disease investigators, and public health nurses—conduct similar investigations regularly. How difficult are some of these investigations? Very.

We checked with Annie Kao, senior epidemiologist with the County Health and Human Services Agency to find out just how hard it is to find the source of E. coli infections.

“Sometimes it’s really challenging,” says Kao, explaining that if the potential source is an item—for example lettuce—which is consumed by the general public, pinpointing where the lettuce came from can be “really difficult.”

On the other hand, if the potential source of exposure is an item not consumed by the masses, like black radishes, identifying it as a potential source of illness would be more likely.

The most common way to acquire an E. coli infection is by eating contaminated food, such as ground beef, unpasteurized milk, fresh produce, and restaurant meals. Other potential sources include contaminated water and personal contact, such as infected people not washing their hands properly.

Some kinds of E. coli can cause diarrhea, while others cause urinary tract infections, respiratory illness and pneumonia, and other illnesses. Some people who are infected with the bacteria may not develop any symptoms, but can spread the bacteria to others.

When an outbreak occurs, the investigation begins to find the cause and, when possible, control and prevent the further spread of disease. If an outbreak is local, it is typically handled by the County. When multiple counties are involved the state gets involved and if more than one state is affected, the CDC usually takes the lead.

EPI investigators interview patients extensively—the form they use is seven pages long—to determine if there is a potential exposure or a connection between cases.

“We need to find out if anything matches between infected persons,” said Kao, who along with EPI Program staff, conducts ongoing surveillance of more than 90 diseases.

One problem in identifying the source of an E. Coli infection is that people cannot always remember what they’ve eaten days earlier. Symptoms typically develop three to seven days after someone becomes infected.

“It’s hard to remember everything we eat,” said Kao. “We ask the questions in a way that helps them recall the items they ate. Sometimes the details are not reported.”

Are people receptive to a stranger asking so many detailed questions about their illness? Most individuals, Kao said, are very appreciative and willing to cooperate.

“We tell them who we are and the purpose of the call,” explained Kao. “We explain the need to identify the source of the illness so that we may prevent others from getting sick.”

For more information on how the County conducts disease surveillance, visit the Epidemiology Program website.